Fast World, Slow Photography: Lewis Baltz

Financial Times Weekend magazine, May 16, 2015

Fast World, Slow Photography

A short essay on the work of Lewis Baltz, written for the Financial Times Weekend magazine photo supplement, May 16, 2015.

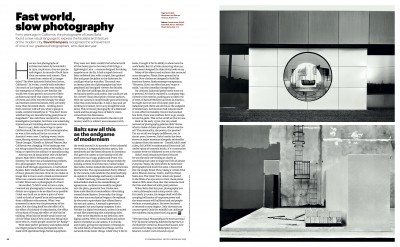

Lewis Baltz, ‘North Wall Steelcase 1123 Warner Avenue Tustin, 1974’ from the series The New Industrial Parks near Irvine, California, 1974

Lewis Baltz, ‘Construction Detail, East Wall, Xerox, 1821 Dyer Road, Santa Ana 1974’ from the series The New Industrial Parks near Irvine, California, 1974

Here are two photographs of architecture taken by Lewis Baltz in 1974. As pictures, they are precise and elegant. As records of built form they are austere and remote. They come from a series of 51 images titled “The New Industrial Parks Near Irvine, California”. In Irvine, a newly built suburban city south of Los Angeles, Baltz was studying the emergence of what is now very familiar: those generic structures of little architectural merit that cluster on the edge of towns and cities. Erected cheaply for small and medium-sized businesses, they are barely more than decorated sheds – nothing about their exteriors will tell you what is going on inside. As Baltz himself put it: “You don’t know whether they are manufacturing pantyhose or megadeath.” He could have ventured in, as an investigative journalist, but there was something mysterious and troubling about those exteriors.

Born in 1945, Baltz came of age in 1960s California and, like many of his contemporaries, he was at first seduced by the art scene of America’s west coast. Crashing waves, heroic trees, blazing sunsets and existential deserts. Think Georgia O’Keeffe or Edward Weston. But California was changing. If the landscape was not being trashed by the creep of suburbia, it was being co-opted by the military or manufacturing.

America was in denial about this unchecked sprawl. Baltz felt it demanded a new artistic honesty, but there was a fundamental problem for a photographer. This new world did not reveal itself through appearances; it hid behind façades. Baltz studied these modular elevations of steel, glass and concrete. How do you make an image that is true to such a blank environment? What can a camera reveal if the world wants to hide? What use is a photograph of a front? He recalled:

“I didn’t want to have a style; I wanted my photography to look as mute and as distant as to appear to be as objective as possible. I tried very hard not to show a point of view. I tried to think of myself as an anthropologist from a different solar system. What I was interested in more was the phenomena of the place. Not the thing itself but the effect of it: the effect of this kind of urbanisation, the effect of this kind of living, the effect of this kind of building. What kind of people would come out of this? What kind of new world was being built here? Was it a world people could live in? Really?”

With their perfect geometry and endless detail one might presume these photographs were made with specialised large-format equipment. They were not. Baltz couldn’t be bothered with all that heavy gear so he used, of all things, a lightweight Leica – a camera designed for taking snapshots on the fly. It had a superb lens and Baltz reckoned that with a tripod, fine-grained film and great discipline in the darkroom he could get what he was after. The result was an immaculate set of photographs that have perplexed and intrigued viewers for decades.

Just like the buildings, his pictures are technically perfect and artless. One could not ask for a better visual description of those surfaces. Here the camera is exceptionally good at showing what that world looks like. It lays it bare and yet nothing is revealed, not in any straightforward sense. This is honest photography of a dishonest world and the strange force of Baltz’s vision comes from the dissonance.

Photography was invented in the mid-19th century and for a while it was consonant with the world around it. As a product of the industrial revolution, it integrated precision optics, fine metalwork and the latest advances in chemistry. This gave the camera a close kinship with the brave new era of cogs, pulleys and levers. You could just about decipher how things worked by looking at them. In architecture, banks looked like banks, homes looked like homes and factories like factories. The unprecedented clarity offered by the camera could celebrate the detail and help to explain it. Knowledge and beauty combined.

It didn’t last long, because the path of industrialism leads to the standardising of appearances. Architecture steadily morphed into the plain, geometric box. Production lines made identical commodities. Advertising created shared desires. Eventually, the things that were once mechanical began to be replaced by electronic equivalents that offered less to the eye and camera. A manual typewriter is photogenic but your laptop computer is not. Neither is a digital wristwatch, unless it is styled to look like something else, something older.

Next to the MacBook on my desk sits a new digital camera. With its metal knobs and robust dials it resembles an old camera. It is chunky and clunky, giving the impression it belongs to the solid family of mechanical things, not the network of electronic things. I didn’t buy it for its looks, I bought it for its ability to show how the world looks. But it’s a little unnerving when an instrument designed for objectivity looks so coy. Many of the objects and surfaces that surround us are deceptive. Plastic floors pretend to be wood. New clothes are designed to look like hand-me-downs. Banks attempt transparency. “Sincerity. If you can fake that, you’ve got it made,” said the comedian George Burns.

By contrast, industrial parks barely even try to pretend. All that is required is a company logo riveted to the exterior, parking and a token row of trees. If Samuel Beckett had lived in America, he might have set one of his later plays in an industrial park. Baltz saw all this as the endgame of modernism. Architecture had reduced itself to cost-effective banality. Once it had reached box form, there was nowhere for it to go, except across the globe. That is the world we live in now.

Back in the early 1970s, the very small network of photography galleries didn’t know what to make of these pictures. Where was the art? The personality, the poetry, the passion? The art world was largely indifferent, too. In recent years, however, Baltz’s series has been shown in major museums alongside minimalist sculpture from the same era – Donald Judd’s steel cubes, Sol LeWitt’s mathematical forms and Carl Andre’s grids of common bricks. It’s a connection curators were too blinkered to see at the time.

Baltz’s work remains pertinent because he was the only one looking so closely at something that came to shape the lives of almost everyone. Today, the sites where he took these photographs look much the same. I discovered this via Google Street View, taking a virtual drive down Warner Avenue, Tustin, and Dyer Road, Santa Ana. The Street View camera car passed in the blink of an eye and, in truth, these places deserve little more than that. But someone took the time and observed with great patience.

When Lewis Baltz died last year, photography lost a stoic philosopher and a sharp social critic. For nearly 50 years, his images dealt with the creeping infiltration of corporate power and the ways money will bulldoze land and people without a second glance. He never hectored or resorted to easy slogans. Only slowness can counter speed. Only the mindful can challenge the mindless. Baltz played the long game.

by David Campany